The Museum of Useless Efforts (Original text: "El museo de los esfuerzos inútiles," by Cristina Peri Rossi)

Translation (SP>EN)

Every afternoon, I visit the Museum of Useless Efforts. I ask for the catalog and sit at the long wooden table. The pages of the book are slightly opaque, but I enjoy perusing them slowly, as if leafing through the pages of time. I never encounter anyone else reading; that must be why the museum employee devotes me so much attention. I am one of the few visitors and she spoils me. Surely she’s fearful of losing her job due to a lack of public interest. Before entering, I take a good look at the sign suspended from the glass door, written in block letters. It reads: Hours: Mornings, from 09:00 to 14:00 hours. Afternoons, from 17:00 to 20:00. Monday, closed. Although I almost always know which Useless Effort I am interested in researching, I request the catalog all the same so the girl has something to do.

“Which year would you like?” she asks attentively.

“The catalog from nineteen twenty-two,” I’d answer, for example.

After a while she reappears with a thick book bound in purple leather and deposits it onto the table, at my chair. She’s very amicable, and if the light from the window seems sparse to her, she herself will turn on the bronze lamp with green tulips and adjust it so the light falls on the pages of the book. Sometimes, upon returning the catalog, I offer a brief comment. I’d say, for example:

“The year nineteen twenty-two was a very intense year. Many people were engaged in useless effort. How many volumes are there?”

“Fourteen,” she answers professionally.

And I study some of the useless efforts of that year, I read about children attempting to fly, men determined to amass wealth, complicated mechanisms that never came to fruition, and numerous couples.

“The year nineteen seventy-five was much more abundant,” she tells me with a trace of sadness. “We still haven’t registered all of the entries.”

“The classifiers will have a lot of work,” I reflect aloud.

“Oh, yes,” she replies. “As of recently they’re only on the letter C and there are already many volumes published. Excluding repeats.”

It’s very curious that useless efforts get repeated, yet classifiers don’t include them in the catalog; they would take up a lot of space. One man attempted flight seven times, aided by different apparatuses; some prostitutes thought they might seek another line of work; a woman wanted to make a painting; someone sought to abandon fear; almost everyone attempted to become immortal or lived as if they were.

The employee assures me that only an infinitesimal fraction of useless efforts ever reach the museum. In the first place, because the public administration lacks funds and practically cannot even complete purchases, process exchanges, or loan museum materials internally or externally; in the second place, because the continually realized, exorbitant quantity of useless efforts would necessitate the labor of many without them expecting compensation or public understanding. Sometimes, desperate for official assistance, they appeal to a private enterprise, but results have been meager and discouraging. Virginia – that’s the kind museum employee’s name, who usually talks with me – assures me that each source consulted always revealed an excess of demandingness and deficit in comprehension, confounding the purpose of the museum.

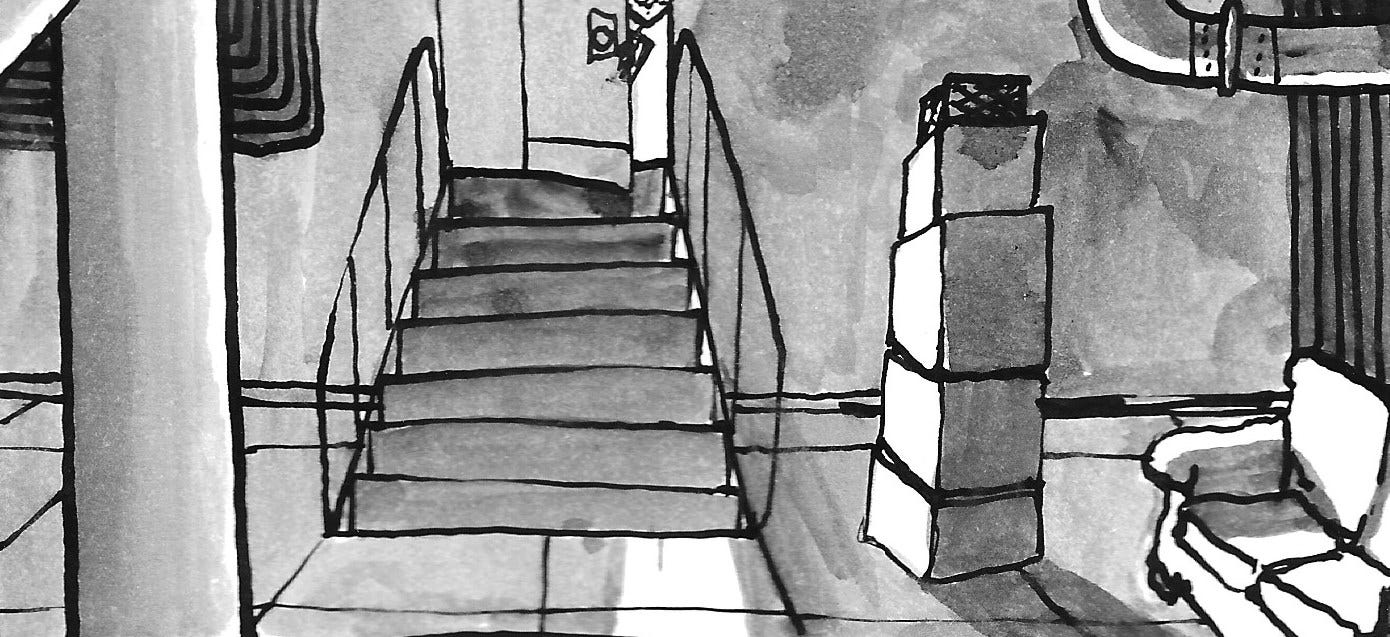

The building rises on the city’s periphery, in a barren countryside full of cats and derelict, where one can still find, only slightly beneath the surface of the ground, cannonballs from an ancient war, the pommels of rusted swords, the jawbones of burros eroded by time.

“Do you have a cigarette?” Virginia asks me with an expression that cannot obscure her anxiety.

I search my pockets. I find an old key, somewhat dented; the tip of a broken screwdriver; the return ticket for the bus; a button off my shirt; a few nickels and, finally, two crushed cigarettes. She smokes surreptitiously, hidden amidst the thick volumes, between flaking book-spines, that demarcator of time against the wall always indicating the incorrect time, generally one passed, and the old moldings lined with dust. Where the museum now stands is believed to have been a fortress, in times of war. They took advantage of the solid stones at its foundation, and some vigas, they strutted the walls. The museum was founded in 1946. They have preserved some photographs of the ceremony, with men dressed in tailcoats, and women in long, dark skirts adorned with estraza and hats with birds or flowers. You could imagine11 an orchestra playing salon music in the distance; the guests have the hybrid solemn-ridiculous air of cutting a cake presented in an official ribbon.

I forgot to mention that Virginia is mildly strabismic. This small defect lends her expression a comic touch that diminishes her ingenuousness. As if the divergence of her gaze were a remark full of humor, floating and detached from context.

The Useless Efforts are arranged alphabetically. When letters run out, they are given numbers. The process is long and complicated. Each one has a shelf, its folio, its description. Moving between them with extraordinary agility, Virginia seems like a priestess, the virgin of an ancient cult disconnected from time.

Some Useless Efforts are beautiful; others, somber. We don’t always agree on this classification.

Leafing through one of the volumes, I found a man who, for ten years, attempted to make his dog speak. And another, who put in more than twenty courting a woman. He brought her flowers, plants, catalogs of butterflies; he offered trips, composed poems, wrote songs, built a house, forgave all of her mistakes, tolerated her lovers, and later, suicided.

“It was an arduous job,” I say to Virginia. “But, possibly, stimulating.”

“It’s a somber story,” replies Virginia. “The museum carries a complete description of the woman. She was a frivolous, fickle, capricious, lazy, and resentful creature. Her intellectual capacity left something to be desired and furthermore, she was selfish.”

There are men who made long journeys pursuing places that do not exist, unrecoverable memories, women who had died, and friends who had disappeared. There are children who, full of fervor, undertook impossible tasks. Like those who dug pits continually inundating with water.

In the museum, it is prohibited to sing as well as smoke. This last restriction seems to affect Virginia as much as the first.

“I’d like to venture a little song every now and then,” she confessed, nostalgic.

People whose useless efforts consisted of attempting to reassemble their family tree, scraping the mines in search of gold, writing a book. Others had the hope of winning the lottery.

“I prefer the travelers,” Virginia tells me.

There are entire sections of the museum dedicated to these journeys. We recreate them within the pages of the books. After a period of drifting across different seas, traversing shaded forests, exploring cities and markets, crossing bridges, sleeping on trains or the benches on platforms, they forget the point of the trip but continue traveling nonetheless. They disappear one day without leaving memory nor trace; lost in a flood, trapped in a subway, or asleep forever in a doorway. No one claims them.

Before, Virginia tells me, there were some private investigators; aficionados who provided materials for the museum. I can even remember a time when collecting Useless Efforts was in style, like philately or ant farms.

“I think the abundance of items is what caused the trend to decline,” Virginia declares. “It’s only stimulating to seek what’s scarce, to find the strange.”

So they would arrive at the museum from different places, ask for information, express interest in some case, leave with pamphlets and go back loaded with stories, which they would print in the (que reproducian en los impresos), attaching the corresponding photographs. Useless Efforts brought to the museum, like butterflies, or rare insects. The story of the one man, for example, who for five years was struggling to prevent a war, until the first shot of a mortar decapitated him. Or Lewis Carroll, who spent his life fleeing the currents of the wind and died of a cold, when he once forgot his raincoat.

I don’t know if I’ve mentioned that Virginia is mildly strabismic. I frequently entertain myself by following the direction of that gaze. I have no idea where it will fall. When I see her cross the room, arms full of folios, volumes, and every kind of document, the least I can do is get up from my seat and go help her.

Sometimes, in the middle of a task, she complains a little.

“I’m tired of coming and going,” she says. “We’ll never finish classifying them all. And the newspapers too. They’re full of useless efforts.”

Such as the story of that one boxer who attempted to claim the title five times, until they disqualified him for a bad blow to the eye. Now, he surely drifts from café to café, in some sordid barrio, remembering the days when his eyesight was good and his fists, lethal. Or the story of the trapeze artist with vertigo, who couldn’t look down. Or the dwarf who wanted to grow and traveled everywhere in search of a doctor who could cure him.

When she grows tired of transferring volumes she sits on a stack of old, dusty newspapers, smokes a cigarette – with discretion, as it’s forbidden – and reflects aloud:

“It will be necessary to find another job.”

Or:

“I don’t know when they will pay me this month’s salary.”

I have invited her to walk in the city, to have coffee or go to the movies. But she has not wanted to. She only wants to talk with me within the gray, dusty walls of the museum.

If time passes, I don’t feel it, engrossed as I am every evening. But Mondays are days of aching and abstinence, on which I don’t know what to do, how to live.

The museum closes at eight at night. Virginia herself turns the simple metal key in the lock, without further precautions, now that nobody would try to break into the museum. Only once did a man do it, Virginia tells me, with the purpose of erasing his name from the catalog. He had made a useless effort in his adolescence and was now embarrassed of it, he didn’t want any lingering evidence.

“We found him just in time,” Virginia recounts. “It was very difficult to dissuade him. He insisted on the private nature of his effort, he wished us to return it to him. In that event I was very firm and resolute. It was a rare item, almost a collectible, and the museum would have suffered a serious loss if that man had fulfilled his purpose.”

When the museum closes I abandon the place with melancholy. At the beginning, the time it took for one day to elapse into the next was intolerable. I had also grown accustomed to Virginia’s presence and, without her, the existence of the museum seemed impossible. I know the director thought so too (that is, he of the bicolor sash, from the photograph), as he’s decided to promote her. Because no position consecrated by custom or law exists, he has created a new position, which in reality is the same, but now has another title. He has named her Vestal of the Temple, not without recalling the sacred character of her mission: to guard, at the entrance of the museum, the fleeting memory of the living.